Infrastructure Week Throwback: Graff Collection Shines Light on Early Water Champion, Artist

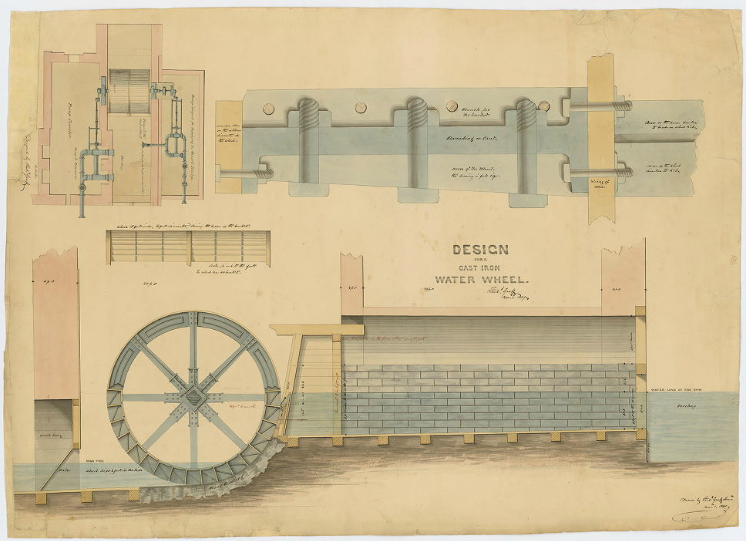

“Design for Cast Iron Wheel by F. Graff” from the Frederick Graff Collection at the Franklin Institute. Credit: Philadelphia Water, the Franklin Institute and The Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

This post explores the foundations of Philadelphia's water infrastructure as we continue to highlight the crucial systems that keep Philly running during Infrastructure Week 2016.

Last year, Philadelphia Water historian Adam Levine joined department employees like long-time engineer Drew Brown on a tour of the Franklin Institute archives, which include a trove of 18th and 19th century drawings by Frederick Graff, an engineer himself with incredible artistic talent who helped to design and operate some of Philadelphia’s earliest water infrastructure. Included in the collection are a number of water-related works by other artists, engineers and cartographers.

Graff’s collection—much of which incorporates watercolor and focuses on hydraulic systems and Philadelphia’s rivers and streams—showcases a fascinating blend of the technical and beautiful, capturing the most finite details of buildings, machines and natural terrain with breathtaking style.

Many of the maps and drawings in the collection are packed with information in the form of notes and finely crafted text, like this map of the Wissahickon by John Cresson and S.B. Linton, which states that the creek was added to Fairmount Park “for the protection of the purity of the water of said creek.”

Because they offer so much information in such an appealing way, and because so few people even know they exist, Levine and Philadelphia Water worked with the Franklin Institute's John Alviti and the Regional Digital Imaging Center at The Athenaeum of Philadelphia to create high quality scans of the Graff drawings and collection and then made them available to the public via the web.

Visiting the digital archives allows you to inspect every drawing in fine detail, and it’s easy to get lost in Graff’s gorgeous world and meticulous notes. Levine talks passionately about the significance of the Graff collection in this short video:

Frederick Graff Drawings at the Franklin Institute from Philadelphia Water on Vimeo.

According to the Philadelphia History Museum, which owns a portrait of this early water infrastructure advocate, the Graff family was filled with “engineers, builders and designers.”

Levine describes Graff as one of the most notable people involved in the creation and operation of the Fairmount Water Works, America’s first steam-powered water supply plant and an important part of Philadelphia Water’s educational outreach today.

In an article about the history of Fairmount Water Works, Levine offers this short bio on Graff:

Graff served as superintendent of the first Philadelphia Waterworks at Centre Square, the site today of City Hall, from 1805 and continued at Fairmount until his death in 1847. Responsible for the design of the Fairmount Water Works facility—the buildings, most of the machinery, the distribution system, the gardens immediately surrounding the waterworks—he, in effect, ran the waterworks.

Graff’s son, Frederick Graff Jr., followed in his father’s footsteps at the Fairmount Water Works, “serving from 1847 to 1856 and again from 1867 to 1872, becoming a leading civil engineer in his own right, and playing a major role in the development of Fairmount Park,” Levine writes.

Together, the Graffs played an important role in Philadelphia’s earliest efforts to create infrastructure that could provide people with safe, clean water. It may be something many people take for granted today, but at the time, Philadelphia’s citizens knew that investing in water infrastructure was a life-saving measure that could prevent rampant outbreaks of deadly diseases.

It was that mindset and urgency that led to the creation of the 6,000-plus mile system of pipes and sewers serving some 1.55 million people today.

Those interested in seeing Graff’s drawings (and most likely those of Graff Jr. too) can do so by visiting the Philadelphia Architects and Buildings website, courtesy of Philadelphia Water.