This has become an iconic photograph, used in books, articles and other publications to illustrate both 19th-century sewer building and, more specifically, the process of building a combined sewer in a stream bed. The stream, Mill Creek, rises near Narbeth, in Montgomery County, PA, and once flowed for five miles through West Philadelphia, from the aptly-named Overbrook railroad station near 63rd St. and City Avenue down to the Schuylkill River along the line of 43rd Street. Today, only the section of creek in Montgomery County remain above ground; within the city limits, the main creek and all its tributaries were incorporated into the Philadelphia sewer system, a 30-year project that began in 1869 and ended around 1900.

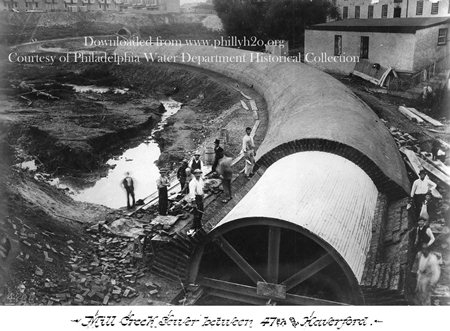

The bottom half of the sewer, called the invert, was already constructed by the time this photograph was taken, and Mill Creek had already been diverted into this artificial channel. The masons are now constructing the top half of the sewer, called the arch. You can see the circular wooden form on which the bricks are being laid, two bricks thick at the top. The form is about 20 feet long, and once the mortar sets the form will be dismantled and reconstructed to build the next 20 foot section.

Some of the workers have stood still for the camera’s long exposure, while those who moved while the shutter was open appear only as see-through ghosts. Two children look to be on their way to or from (or maybe skipping) school to observe the work. In the upper right is a textile factory building that had used the water of Mill Creek for industrial processes such as washing, bleaching and dyeing; now it will have to use city water for these purposes. On the left a remnant of the natural creek bed is visible, and in the background are houses that have already been built right up to the edge of the work in progress.

After the sewer was completed, the land was filled about 30 feet above the original stream bed, the grid of streets was laid across the valley, and this once-rural area was transformed into part of urbanized Philadelphia by the development that quickly followed. The sewage of these new houses and businesses, carried by a system of tributary pipes, flowed into the Mill Creek Sewer, along with stormwater and the remnant flow of the above-ground portion of the stream. With the creek buried out of sight, it quickly dropped out of mind, and people who lived in the neighborhood called Overbrook, or even one called Mill Creek, could not tell you the source of those names. Meanwhile, forgotten or not, the old mill stream, now conscripted to the dirty job of carrying away a neighborhood’s wastes, still rolls on, beneath the streets.