From the Philadelphia Water Archives: A bulletin board outside the archive room at 12th and Market.

When you think about the truly priceless value of clean drinking water—something we all need to survive—compared to what it actually costs, tap water may well be the most undervalued commodity out there.

At 7/10ths of a cent per gallon, Philadelphia Water’s tap is an incredibly good deal, especially when you consider how much work we do to make sure 1.7 million customers have constant access to this resource.

And, since we distribute about 275 million gallons of drinking water every day, we think about the cost quite a bit.

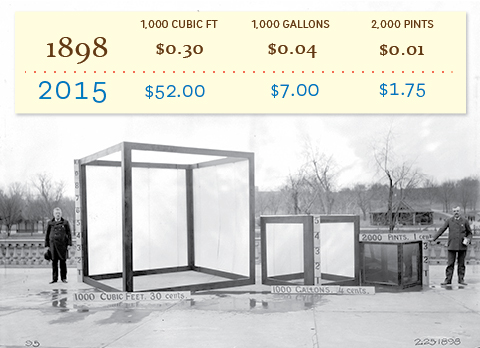

We came across a photo in the archives that proves we’ve been thinking about the cost of drinking water (and how to communicate that to our customers) for a long time:

A Feb. 25, 1898 photograph from the Philadelphia Water archives showing the cost of drinking water. Credit: Philadelphia Water.

In this 1898 photo, taken at the Fairmount Water Works, officials created what’s essentially a 117-year-old infographic by posing with various containers of water and providing the cost of each by volume.

It got us thinking: what would that same amount of water cost today? Naturally, we did the math, and here’s what we found:

Cost of drinking water in Philadelphia in 1898 vs. 2015. Credit: Philadelphia Water.

Adjusted to today's value using the Consumer Price Index (a dollar in 1898 would be worth a bit more than $28 in 2015), these numbers represent a more than 500 percent increase in the cost of drinking water.

What’s behind the spike? The answer to that question comes from another question: how on earth did they provide 1,000 gallons of water for just $00.04 ($1.15 in 2015 dollars)?

Well, let’s just say that what they called “drinking water” in 1898 was a far cry from what Philadelphians expect when they turn on a faucet today. There was no guarantee that the water wouldn’t make you sick, let alone look clean.

Our historian, Adam Levine, says water treatment at the time was pretty much non-existent: river water was pumped to reservoirs where, if demand happened to be low enough, it had time to clarify before going off to homes. High demand, however, often meant the water didn’t even have time to settle, and the results could be rather ugly.

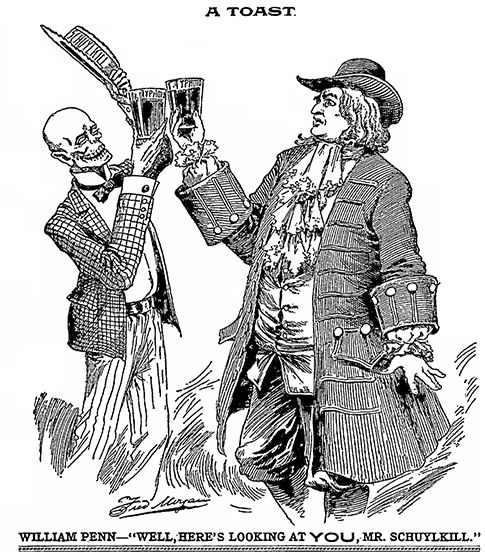

"I have come across a number of cartoons from the period that talk about the water running out of pipes as black as ink, due to the coal dust (washed down from upstate coal mines) suspended in the river water after heavy rains," Levine says.

For a Throwback Thursday double-dip, let’s take a look at one of those cartoons:

A cartoon from August, 1898 addresses typhoid in Schuylkill River drinking water. Credit: Philadelphia Water.

Ouch.

Today, we still let the water settle—but that’s just one step in complex process that involves filtration, treatment for pathogens, and lot and lots of testing. We were one of the first cities to use filtration, and the advent of chlorination in the early 1900s helped to make widespread water-borne illnesses a thing of the past—a past that, as we see here, meant very cheap but dangerous drinking water.

“Our largest [budget] items are for chemicals and energy (electricity and natural gas),” says Debra McCarty, Director of Operations for Philadelphia Water. “The process of treating river water to become potable water has become more complicated over the years. The standards to which we treat drinking water are far higher than ever. Regulations continue to change, and we continue to meet them.”

All that work (check out this graphic for a look at how we treat tap water) adds costs to the price of drinking water, but at $00.07 for every 10 gallons, we think it’s a pretty good deal for something truly priceless—safe, tasty tap water 24/7.

The value seems like an even better deal when you consider the cost of drinking bottled water.

The American Water Works Association estimates bottled water costs Americans anywhere from 300 to 2000 percent MORE per gallon than the average gallon of tap water.

So make the smart choice: drink tap water, save money, and be glad you aren’t living in the 1890s!

Want to stay up to date on the latest Green City, Clean Waters news and get important Philadelphia Water updates? Subscribe to our monthly newsletter now by clicking here!